|

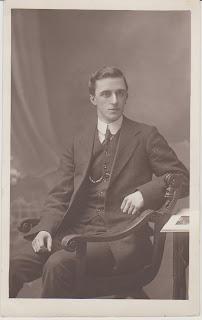

| Mark Hovell - a new portrait. |

I was aware when I bought my copy of the book that it had been given by Fanny to Lilas Nightingale (nee Drinkwater), who had known Mark Hovell before the war as secretary of Manchester University Education Society.

The book is dated January 1918 and inscribed "With love from Fanny". Also enclosed is a newspaper cutting marking the second edition which describes Hovell's life and work and has a handwritten note about his friendship with Nightingale.

What I hadn't realised until the book arrived and I opened it, was that there was also a postcard-format photograph of Mark Hovell. The only other picture of him I have seen shows him in uniform. I have reproduced this new photograph here. On the back is written "For Lilas (from Mark)".

Hovell's book has been much criticised in recent years. Based largely on contemporary accounts by Francis Place and others hostile to the leadership of Chartism, it paints Feargus O'Connor as a demagogue who led the movement to destruction.

It took decades to rescue O'Connor's reputation and to recast Chartism not as a worthy cause taken over by an illiterate rabble of the dispossessed but as a coherent and consciously working class political party.

But perhaps it is unfair to blame Hovell for this. In Edwardian England, he was breaking new historical ground even by working on Chartism, and like all historians he was the product of his background: in this case a Fabian socialist sensibility which recoiled from revolutionary ideas.

And he can hardly be blamed for the judgements made in the second half of the book, of which he was not the author. For his time, Tout was something of a radical in academic politics. But as a medieval specialist, he was hardly best equipped for the task.

No comments:

Post a Comment